We asked Dr. Jason Evans, Professor of Environmental Science and Studies at Stetson University, to share his expertise about compound flooding risks from Hurricane Milton along the Florida east coast and into the St. Johns River. Here is his input:

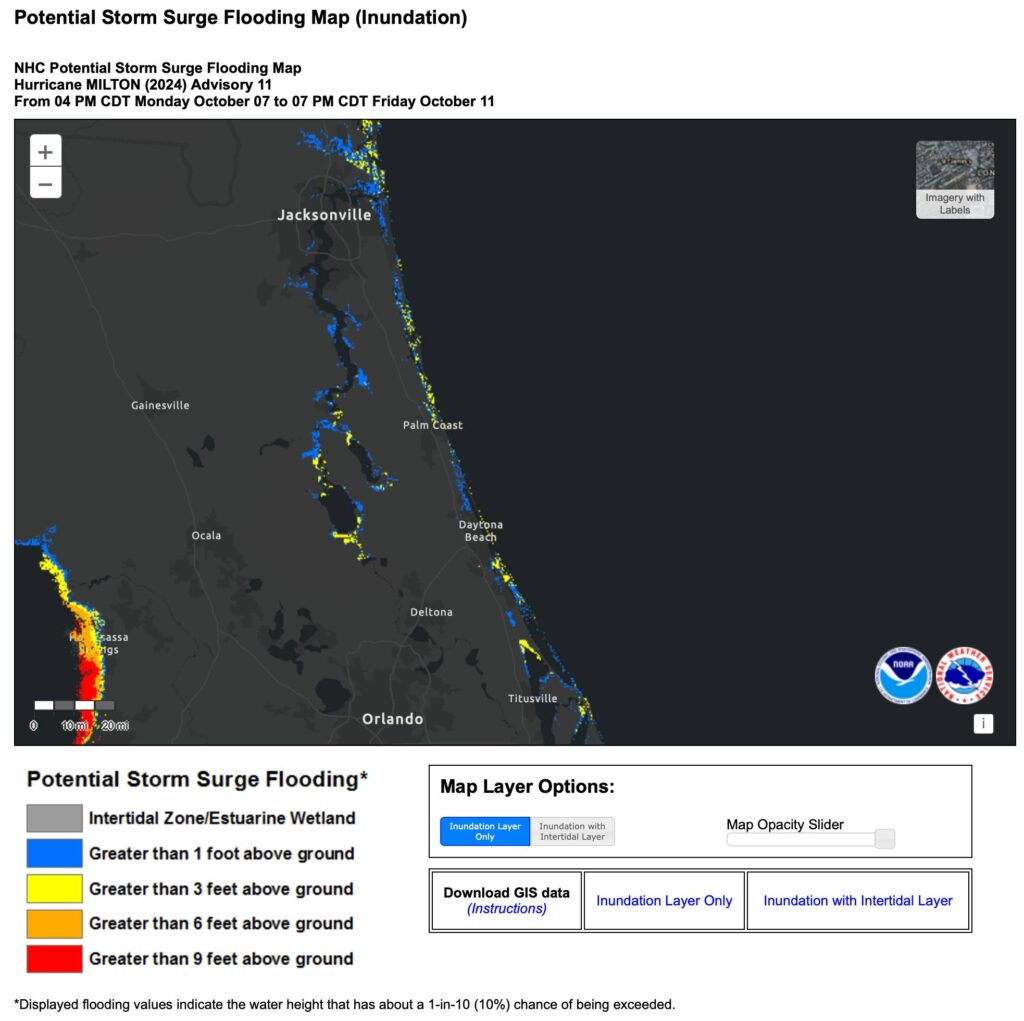

As the hurricane crosses and exits the state, coastal areas to the north of the eye will be susceptible to pretty substantial storm surge in the 3-5 foot range. Also note that big lakes within the St. Johns River and elsewhere in central Florida (e.g., Lake George, Lake Apopka, Lake Tohopekeliga, etc.) can also experience inland surge from a big storm like Milton, especially if the eye wall goes right over them.

The east coast storm surge will not be nearly as high or devastating as what occurs on the gulf coast, which unfortunately threatens to be at Hurricane Katrina levels of impact. As we saw during Hurricane Ian, though, a gulf-landing storm can also bring damaging floods to our area, especially when the storm brings torrential rains. The storm surge makes this rainfall flooding even worse within coastal areas and along much of the St. Johns River for several reasons.

First, the storm surge will “back up” many stormwater systems with saltwater to a point where they will not allow for rainfall to drain effectively. This is because many of our stormwater systems unfortunately drain directly into rivers and coastal estuaries in systems designed and built more than 50 years ago. In some cases, the stormwater systems may even back flow into streets with saltwater from the storm surge, effectively amplifying the flooding from rainfall.

Second, the torrential rainfall, storm surge, and heavy winds will also bring substantial amounts of leaf matter and other debris into the stormwater systems, further impairing their ability to move water out even after the storm surge subsides. In other words, at the very time that these systems are needed the most, they are susceptible to partial or complete failure.

Third, the St. Johns River is a very strange river. Because it is so flat, a storm surge at Jacksonville can stop or even reverse the flow of the river astonishingly far upstream. As the watershed is hit with torrential rain, higher water from a large storm surge could conceivably back up the river flow as far away as Lake Monroe for a day or more. The St. Johns already flows very sluggishly, but the storm surge basically makes it even more sluggish. Jacksonville is especially susceptible to this type of compound flooding, as we saw several years ago with Hurricane Irma. But the effects can go much further upstream than most people would think.

I’ll finish by noting that the St. Johns has a large watershed that stretches from Vero Beach to Jacksonville. It appears that much of this watershed is at risk of getting 6-10″ of rain. We’re already at minor to moderate flood stage in some parts of the river, and this huge input of water from Milton will cause all sections of the St. Johns to rise substantially. Remember, after Hurricane Ian it took several weeks for the St. Johns to crest at record heights at many gauges. It’s too early to know if any of Ian’s river height records will be broken by Milton, but I certainly wouldn’t rule it out.

Please be safe out there. Remember to run (evacuate) from water, and hide (in a well-built structure) from wind.

– Dr. Jason Evans, Professor of Environmental Science and Studies at Stetson University

Map that describes potential storm surge inundation from the storm. Credit: National Hurricane Center